Learning the grammar of video

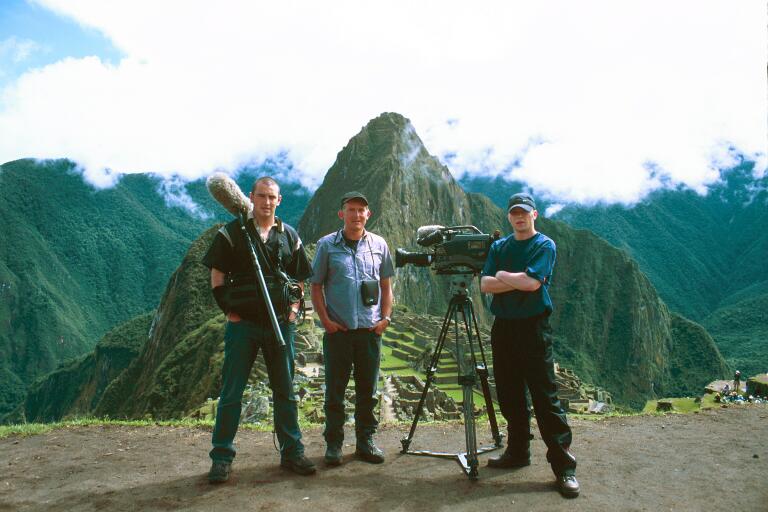

/Adam Salkeld filming for the BBC with documentary crew - Machu Picchu, Peru

Every language has its grammar and video is no exception. DLA co-founder Adam Salkeld examines how we harness visual grammar to make our authentic videos more effective.

Humans have evolved powerful visual memories. We all experience the act of remembering in a series of images or even mental “video clips”. The power of visual recall is strong - when President Trump removed the FBI’s Director James Comey this week many of us instantly recalled the “You’re fired!” scenes from The Apprentice TV show. Shots of a drowned child did more to engage the public and politicians in the refugee crisis than countless speeches or articles.

Visual memory is closely tied to the imagination and educators often feel uneasy about the raw power of the visual media. We fear that it is an uncontrolled force. We worry that it feeds our emotional faculties more than our rational intellectual ones. The result is that we are tempted to play it safe. Where learning videos might engage or inspire, we see too many that simply replicate the printed page on screen, missing all the potential value that video can add for learners. This does not need to be the case. Knowledge conquers fear. If we learn how something works, we can control it. At DLA we are passionate about trying to demystify the production of high-quality authentic video so that we can make the most of it in the learning arena.

Video is a language, and just like any other, it has a grammar as its structural architecture. When we learn any new language, the process of understanding its grammar is the key to unlocking potential and fluency. In film and video, shots are the words; sequences the clauses and sentences; moves, cuts, and mixes the punctuation. We can use the building blocks of video grammar to express the past as well as the present and to develop styles and genre. We can fine-tune our shots to manipulate pace and remove redundancy. We can learn when putting two shots together seems clumsy or looks elegant. The grammar and syntax of video allow us to develop character and create compelling narratives - both key to engaging learners in and out of the classroom. When we are comfortable about the rules, we can be bold enough to break them. Above all, only when we understand the grammar of video, can we exercise control. It is there to help us express ourselves clearly to our audience of learners.

I had my grammar lessons 25 years ago at the BBC. That was a time when a broadcast-quality camera cost as much as a family house and an editing suite even more. Sharing your video meant broadcasting it on a TV channel. The whole process took scores of highly qualified people. I embarked on a fascinating journey. Like generations of BBC graduate trainees before me I had come to television from a traditional academic background. I was used to learning and expressing myself through words - reading, writing, listening and discussing. That all had to change. The two-year BBC ‘bootcamp’ was designed to wean us off text and onto thinking in moving pictures. It was an exhilarating experience.We learned from, and worked alongside, some of the industry’s most talented and inspirational filmmakers, storytellers and craftspeople. In edit suites, studios and on location we practised this new language until we were considered fluent enough to be let loose making programmes for the airwaves. And since then I have never stopped learning new vocabulary or idioms in the language of film.

More than anything else I have learned to appreciate the power of film and video as a medium – probably the most effective form of mass communication we humans have yet invented. It captures moments, emotions and stories forever. But it doesn’t just happen on its own – as anyone who has ever sat through an unedited wedding video can testify! You have to squeeze, craft and concentrate reality into an effective piece of film or video. Filmmakers have a whole toolbox of techniques to help them, ranging from camera and editing styles, to music, visual effects and sound design. Sometimes we go overboard with tricks, at others we do not apply our craft enough. The most talented learn the balance and never forget that they are telling a story.

I became interested in using the skills of filmmaking in digital education about 15 years ago. I was fascinated by the way in which the techniques of television could be harnessed to engage learners in the then relatively new medium of e-learning. The best teachers I could remember told great stories, so surely using the narrative power of filmmaking and combining it with digital interactivity would create the best learning resources. Despite having worked on some great learning projects since then I can’t help thinking that the best of video learning is still to come. At DLA we are passionate about the authentic videos we make. We hunt out the stories and characters from the world’s best broadcast and internet video. We use our knowledge of video grammar and style to re-craft it into effective learning video, with a clear pedagogy, that is designed to engage learners and stimulate reflection and activity. Who said learning grammar was boring?